What Is a Monopoly in Economics?

What is a monopoly in economics? A monopoly in economics is defined by a single entity controlling market pricing and supply, in stark contrast to perfect competition where numerous firms compete. This dominance allows the monopolist to employ pricing strategies, such as single-price and price discrimination, tailoring prices to different demand elasticities to maximize profits. Understanding what a monopoly is in economics is crucial for grasping its effects on market dynamics and regulatory policies.

Join over 2 million professionals who advanced their finance careers with 365. Learn from instructors who have worked at Morgan Stanley, HSBC, PwC, and Coca-Cola and master accounting, financial analysis, investment banking, financial modeling, and more.

Start for FreeA monopoly represents a distinct shift from perfect competition—marking a unique setup in market structures. Unlike the myriads of small firms in an ideal competition that compete for market share, what is a monopoly in economics? A monopoly is characterized by a single seller who dominates the market, setting prices and controlling supply. Where perfect competition is a battleground for numerous competitors, a monopoly sees one entity ruling the market.

Monopoly Characteristics

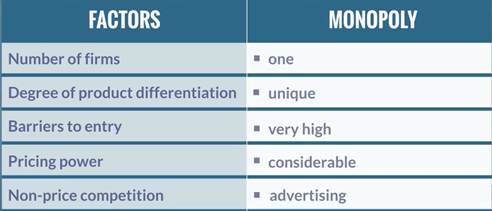

In this context, a monopoly market structure features only one dominant player with no actual competition, controlling both the demand and supply. This leads to a downward-sloping demand curve. High barriers to entry further cement this control, effectively preventing potential competitors from entering the market.

The company’s product is unparalleled and primarily stands out due to non-price strategies like advertising. As a monopoly, the firm possesses significant pricing power, allowing it to set any price. But ensuring customer affordability is crucial—making pricing a strategic decision for monopolies.

Note the following concise table summarizing the key characteristics of a monopoly.

Pricing Strategies in Monopolies

Generally, there are two pricing strategies that companies may undertake in this market structure:

1. Single-price strategy

2. Price discrimination

Single-Price Strategy

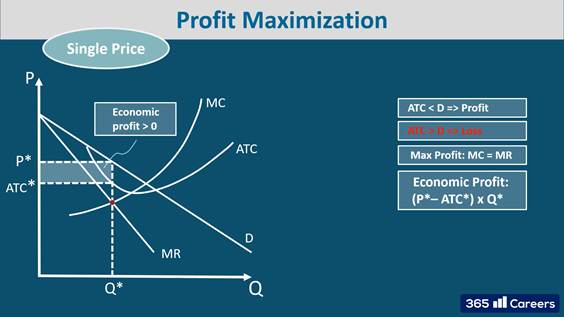

The single-price strategy is observed when all customers are offered the same price. The following graph illustrates a monopoly’s demand curve with a downward slope and a marginal revenue (MR) line below it. Profits occur when the average total cost (ATC) exceeds demand (D).

If the average total cost exceeds demand, it results in a loss. Notably, the marginal cost (MC) curve intersects the average total cost curve at its lowest point.

Profit maximization is reached when the marginal cost equals the marginal revenue (MR), as in any other market structure. A low marginal cost will keep increasing until both lines become equal. From that point, we draw a horizontal line up to get the average price (P*) and average total cost (ATC*), determining the area of total economic profit.

In this situation, the maximum (economic) profit is the difference between the price charged to customers and the average total cost times the quantity:

Economic Profit = (P* – ATC*) x Q*

Price Discrimination

In responding to the question, “What is a monopoly in economics?” the second pricing strategy, price discrimination, is commonly employed in monopolies. With this approach, various customer groups are charged differently. Price discrimination can only be applied if customers cannot resell the products they buy and if two groups of people have different demand elasticities. Examples of price discrimination include reduced-price cinema tickets available on Thursdays or hotel promotions for a weekday stay.

Companies differentiate between several groups of customers, which increases their overall profit. They charge the highest price that each customer group is willing to pay. The buyers with high demand elasticity would be charged relatively lower because the quantity they buy is susceptible to price changes. Those with inelastic demand curves must pay higher prices for the same products.

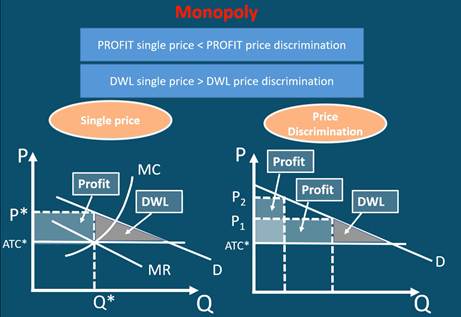

How does the total profit change compared to single pricing?

To understand how total profit shifts compared to single pricing, we must discuss deadweight loss (DWL). DWL arises from market inefficiencies when a uniform price is set for all customers—leading to revenue losses from excessively high prices.

When a monopolist adopts single pricing, significant DWL occurs because customers with high demand elasticity purchase less. Conversely, reducing prices can increase profits and minimize DWL.

Unlike single-price strategies, price discrimination minimizes the deadweight loss:

Ultimately, perfect price discrimination yields quantities equivalent to those in a competitive market.

Artificial Monopolies

Companies benefit more from operating in a monopoly than in a competitive market because they can charge higher prices. Often, firms invest substantial resources to establish monopolies—known as rent-seeking.

Considering political lobbying, what is a monopoly in economics? Companies might invest heavily to secure a license granting a monopolistic market share. If successful, this strategy yields significant economic profits, making the effort worthwhile.

Fortunately, such practices do not remain unregulated. Authorities aim to discourage the occurrence of monopolies. Instead, they try to improve the overall market efficiency, which benefits customers the most. Regulators try to stimulate fair competition by controlling monopoly pricing or reducing artificial entry barriers, such as licensing requirements, quotas, and tariffs.

Governments can adopt one of two strategies:

1. Average cost pricing

2. Marginal cost limitations

Average cost restrictions are quite common in practice. They allow companies to charge prices up to the average cost of production. Average costs, however, may be higher than marginal costs—resulting in prices for selling additional units of a given product.

Marginal cost pricing regulation, on the other hand, aims to wipe out deadweight losses. In this case, a monopoly would recognize losses and exit the market. To prevent this from happening, governments offer monopolists a subsidy to obtain an expected profit.

Natural Monopolies

A natural monopoly also addresses the question, “What is a monopoly in economics?” This monopoly arises when a company expands production and experiences decreasing marginal costs across all levels of consumer demand—often due to substantial initial investments. Common examples include mobile, electricity, and water suppliers.

When an additional customer seeks to purchase an additional product or service, the marginal cost of such a company decreases. And if another firm enters the market, it will increase the cost of production directly because of the lack of economies of scale. As a result, customers will be charged higher prices. Therefore, it’s economically sensible for some natural monopolies to exist. To ensure fair trade, many governments allow some monopolies to operate.

Navigating Monopoly: Strategic Profit Maximization

What is a monopoly in economics? From a firm’s perspective, a monopoly market structure provides an opportunity for high profits, which are further increased by price discrimination. Make sure you draw a line between monopoly and monopolistic structures. A monopoly has only one firm dominating the market, while a monopolistic structure includes a few players selling close substitutes.

Since market structures and an economy’s cyclical expansions and contractions are interrelated, we recommend you examine the business cycle.

Understanding these nuances between monopoly and monopolistic market structures is crucial, and by joining the Financial Analyst platform, you’ll gain deeper insights into how these dynamics can affect your investment strategies.