How to Prepare Financial Statements

Learning how to prepare financial statements is essential for analyzing and comparing company performance across industries and regions. This guide explains key adjustments—like depreciation methods, inventory valuation, and intangible assets—that reveal a business’s true financial health.

Join over 2 million professionals who advanced their finance careers with 365. Learn from instructors who have worked at Morgan Stanley, HSBC, PwC, and Coca-Cola and master accounting, financial analysis, investment banking, financial modeling, and more.

Start for FreeMastering financial analysis involves more than just crunching numbers—it requires a deep understanding of financial markets and an awareness of the psychological biases that can influence decision-making. At the core of this skillset lies the ability to interpret and prepare financial statements. For anyone aiming to become a proficient finance professional, knowing how to prepare financial statements and analyze a company’s financials is not just useful—it’s essential.

Differences in Financial Statements

When analyzing company financials, it’s vital to remember that firms often apply different accounting policies. These differences arise from local financial reporting standards or choices made by company management. For example, a company based in the US may report under the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), while one in Europe is likely to follow International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Even though these standards aim to present a fair financial picture, they do so in different ways.

As a result, investors and analysts who want to compare companies across regions must be prepared to adjust to these differences. The goal is to make the financial data more comparable—even if the original reports are structured differently.

What Does It Mean to Adjust Financial Statements?

Adjusting a financial statement involves modifying the reported data to create a like-for-like comparison between companies. This process often requires a solid understanding of accounting rules, knowledge of how to prepare financial statements, and judgment to identify which items need aligning. How a company records depreciation, inventory, or intangible assets can significantly impact its performance on paper.

Key Areas Where Adjustments Are Needed

Depreciation Methods

One of the most common adjustments involves depreciation. Companies often use different methods to account for the wear and tear of their assets. This can lead to very different expense patterns and profit margins even when companies own identical assets.

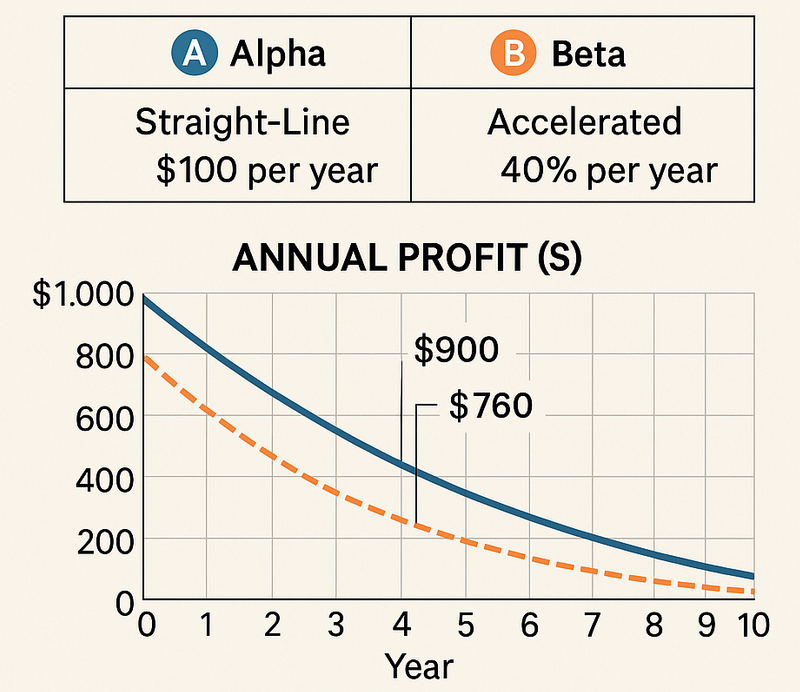

To illustrate, consider two companies (Alpha and Beta) that each purchase a $1,000 asset with a 10-year useful life and no salvage value. Alpha uses the straight-line method, recording $100 in depreciation each year. Beta uses an accelerated process, writing off 40% of the asset’s remaining value annually.

While both companies end up with about the same total depreciation after 10 years, their annual profits look very different along the way. For instance, in Year 4, Alpha might show $900 in net income, while Beta reports just $760. Over time, however, the gap narrows. By Year 9, Beta’s depreciation has slowed substantially, and its profit comes close to matching Alpha’s—though it still remains slightly lower.

This variance doesn’t reflect better or worse performance—it simply reflects different accounting methods. For a fair comparison, an analyst would adjust Beta’s figures to reflect the straight-line method.

Inventory Accounting

Another area requiring adjustment is inventory valuation. A company in the US might use the LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) method, while a firm in Australia or Europe uses FIFO (First-In, First-Out). Understanding these methods is essential when learning how to prepare financial statements, as they produce different results—especially when prices are rising or falling.

In such cases, analysts look at the LIFO reserve (a disclosure required by GAAP) to translate the reported numbers into FIFO terms and allow for direct comparison with companies following IFRS.

Intangible Assets and Goodwill

The treatment of intangible assets can also differ. Under IFRS, companies can revalue intangibles upward, while GAAP does not permit this. Instead, US standards allow only impairments. These differences affect equity and net income. When analysts want to strip out these effects, they may remove revaluation gains or impairment losses from the reports to level the playing field.

When companies undergo mergers or acquisitions, their financial statements may change dramatically due to the different accounting methods used in the transaction. How goodwill is calculated, how assets are revalued, or whether full or partial consolidation is used impacts financial results.

Analysts must be ready to spot these changes and adjust accordingly—especially if they compare the company’s performance before and after a merger.

Putting Adjustments into Practice

Although financial statements may appear objective, they often reflect subjective accounting choices. That’s why skilled financial analysts go beyond surface-level numbers. They make adjustments where needed—especially for depreciation, inventory methods, and intangible assets—to ensure they compare performance, not just accounting. In short, adjustments allow you to answer a key question with confidence:

Are the differences in financial results due to operations—or just bookkeeping?

Making Financials Comparable

Understanding and adjusting financial statements is critical for any analyst aiming to compare companies accurately across borders, industries, or accounting standards. Gaining a firm grasp of how to prepare financial statements helps reveal the underlying methods, estimates, and assumptions that can distort comparisons. While financial reports may seem straightforward at first glance, they often tell a more complex story.

By learning to identify key areas—such as depreciation, inventory valuation, intangible assets, and M&A accounting—analysts can strip away these inconsistencies and uncover a business’s true economic performance. Ultimately, this ability transforms raw financial data into reliable insights for sound decision-making.

To build this expertise with practical, hands-on guidance, consider joining the 365 Financial Analyst platform—where structured courses and real-world case studies can help sharpen your analytical edge.