What Are Forward Contracts, Futures Contracts, and Swaps?

Join over 2 million professionals who advanced their finance careers with 365. Learn from instructors who have worked at Morgan Stanley, HSBC, PwC, and Coca-Cola and master accounting, financial analysis, investment banking, financial modeling, and more.

Start for Free

There are five main types of derivatives contracts we will study: forwards, futures, swaps, options, and credit derivatives.

As we said in our previous article, forwards, futures, and swaps are forward commitments. This means they are contracts requiring each party to perform a specified action in the future. Whereas, options and credit derivatives are contingent claims.

Given the topic’s volume, we’ll break it down into two parts. In this article, we will deal with forward commitments – forwards, futures, and swaps. And in the next article, we’ll continue with options and credit derivatives.

So, what do we mean by forward contracts?

Forward contracts are an over-the-counter derivative contract in which two parties agree on the future sale of an underlying asset. The buyer is referred to as the LONG position, while the seller is the SHORT position. They simply define a specific future date when the transaction will take place. In addition, the selling price of the underlying asset is predetermined at the time when the document is signed.

The transaction we saw earlier, in which a grain producer enters in an agreement to sell their harvest at a future date, was an example of a forward.

Now, we’ll find out more about the mechanics of the transaction.

Usually, a payment at initiation isn’t necessary by either party. The buyer and the seller agree on a forward price i– that is the price at which the exchange of the underlying asset will take place after a period of time.

There are, of course, different scenarios of what might happen in the future. One option is for the price of the underlying (grain in our example) to increase. In that case, we have a contract that allows us to buy the crops at a lower price and, hence, we say that the forward settlement has a positive value. Alternatively, the price of grain could go down, but we’ll still have to buy at the predetermined price specified in the forward – therefore, we say that the forward agreement has a negative value.

In theory, when the forward expires, the short position should deliver the underlying asset to the long which needs to consequently pay the pre-agreed price. Think of it as a regular sale of a product, which occurs in the future instead.

In practice, however, forward contracts, are often settled in cash.

We can have:

- non-deliverable forward ( an NDFs),

- cash-settled forward contracts,

- or contracts for differences.

In these situations, we don’t have an exchange of an underlying asset, only the difference in prices is paid in cash.

As you understand, an important characteristic of forward contracts is that they bear counterparty risk. They are typically traded over the counter, which means that there is no clearinghouse that absorbs the counterparty risk.

So, to reduce their exposure, the two sides to the contract must carefully evaluate each others’ profiles prior to signing the agreement. If either one believes the involved uncertainty is significant, they may require a performance bond. This is a guarantee, usually provided by a third body like an insurance company, to ensure payment in case the opposing party in a derivative contract defaults on its obligations. Another possible solution is the deposit of collateral in a fiduciary account. Should the party that has provided collateral defaults, the other side can keep that monetary deposit as a form of compensation.

This is what we need to know about forwards for now.

Let’s consider the next type of forward commitment—futures contracts.

A futures contract is a standardized forward contract that is traded in regulated exchange.

Unlike forward agreements though, futures are highly governed and contracts are guaranteed by a clearinghouse.In that regard, you don’t need to worry about counterparty risk as much as you would with forwards.

One slight difference with respect to forward agreements (where no initial payment was required), is that, here, the clearinghouse requires margin – some money needs to be deposited to cover potential decreases in value of the position of either party. If the underlying asset fluctuates to a greater extent, the clearinghouse could call the one with insufficient margins and request the payment of additional funds.

Prevalently, clearinghouses practice the so-called mark-to-market, meaning that parties need to settle their gains and losses in cash. As a whole, both mark-to-market and the proivision of an initial margin help lower default risk for the clearinghouse.

The third type of forward commitment we’ll cover is referred to as “Swap contract”.

Now, what is the core of a Swap trade?

This is an agreement in which two parties agree to exchange (or swap) cash flows or other financial instruments over multiple periods (the time frame could be months or even years). Swaps are typically used to manage risk.

Very much like forwards and futures, a Swap contract’s value is 0 at inception; and then, throughout the life of the contract, the gain of one party turns into a loss of the same amount for the other.

The most popular among them are interest rate and currency swaps, where parties exchange cash.

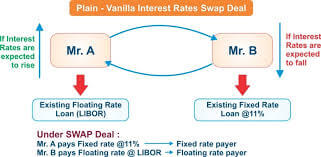

Interest rate swaps have gained massive popularity in the banking world of today. They allow financial institutions to manage interest rate risk. Most frequently, parties exchange a fixed interest rate payment and a variable interest rate. We call that a plain vanilla interest rate swap.

Think of individuals who prefer to pay a fixed interest rate and have certainty regarding the future. Based on these presuppositions, some decide to enter in an interest rate swap agreement with a bank which, in turn, prefers to keep its liabilities flexible (by paying a floating interest rate). In that instance, if interest rates rise, the bank would be able to cover the increased obligations by charging higher interest rates on its loans. Here, an interest rate swap would help both participants manage risk and move forward confidently.

A currency swap, on the other hand, is a transaction in which two parties exchange principal and interest payments in different currencies.

Suppose we have a currency swap contract in which we exchange 100,000 euro for the spot rate equivalent in dollars, let’s say 110,000. At initiation, the European agent will provide 100,000 euro, while the US counterparty 110,000.

Throughout the life of the agreement, each participant pays interest on the swapped amount. The European party settles interest transactions in dollars, and the US one services the contract in euro.

At the end, each of them receives back the original amount it provided – the US party recovers the initial $110,000, and the European gets back 100,000 euro.

After all, who benefits from a currency swap?

Basically, anyone who wants to make sure that currency risk would not play an important role in their operations. If your company pays its costs in dollars and receives revenue in euro (because your target market is in Europe), you might as well enter in a currency swap agreement and hedge for the excessive exposure towards the euro.

In the next articles, we’ll talk about options and credit derivatives.