The Cash Conversion Cycle: Measuring Working Capital Efficiency

The cash conversion cycle (CCC) is a key metric for assessing how efficiently a company turns inventory and receivables into cash. By understanding and optimizing the CCC, businesses can improve liquidity, reduce reliance on external financing, and strengthen overall financial health.

Join over 2 million professionals who advanced their finance careers with 365. Learn from instructors who have worked at Morgan Stanley, HSBC, PwC, and Coca-Cola and master accounting, financial analysis, investment banking, financial modeling, and more.

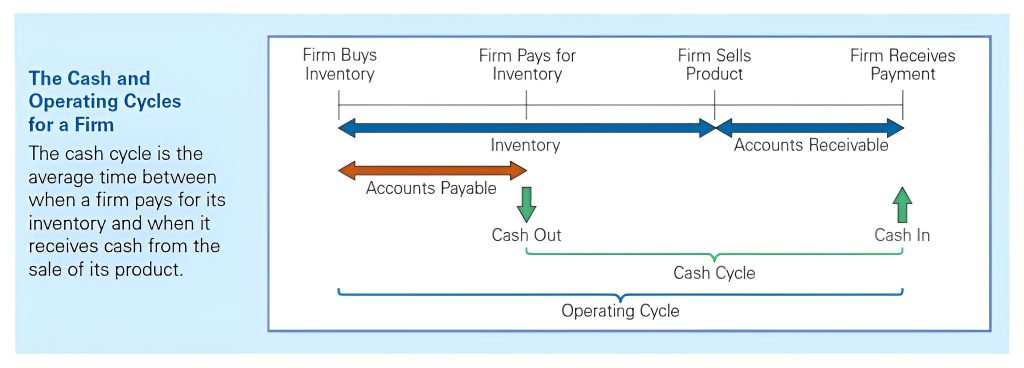

Start for FreeThe cash conversion cycle (CCC) and the operating cycle are two key tools used to evaluate how effectively a company manages its working capital. These measures reflect how long it takes a business to convert its investments in inventory into cash flow from customer sales. By understanding the time involved in each step of the production and sales process, firms can improve liquidity, reduce reliance on external financing, and operate more efficiently.

Let’s explore a typical firm’s production timeline and how it influences both the operating and cash conversion cycles.

From Inventory to Cash: How the Cycle Works

A firm’s working capital process begins when it acquires inventory, often on credit. These are typically raw materials required for production. After processing the goods into final products, the company must then wait until a sale is made. Often, sales are offered on credit—meaning there’s a delay between the sale and actual cash collection.

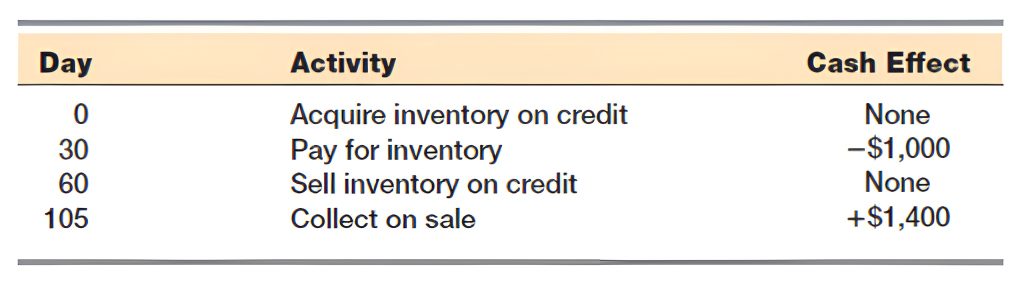

The table below helps visualize this timeline and introduces the concepts of the operating and cash conversion cycles:

To better understand the operating cycle, let’s look at a simple example. Suppose a company acquires inventory on Day 0 and pays $1,000 for it on Day 30. It sells the inventory on Day 60 for $1,400 but collects the payment only on Day 105. The timeline of these events is shown below:

Corporate Finance by Jonathan Berk and Peter DeMarzo

From this timeline, we can identify two key components of the operating cycle. The first is the inventory period—the 60 days between acquiring the inventory and selling it. The second is the accounts receivable period—the 45 days between the sale and the cash collection. Together, they form the operating cycle.

The operating cycle is calculated as:

Operating Cycle = Inventory Period + Receivables Period = 60 days + 45 days = 105 days

This means it takes 105 days from the time raw materials are purchased to the point when cash is collected from customers.

The Cash Conversion Cycle

While the operating cycle tracks the whole process from inventory purchase to cash collection, it does not account for the fact that the company does not pay for the inventory immediately. In our example, the firm pays for the inventory on Day 30. Therefore, the actual time that the firm’s cash is tied up is only from Day 30 to Day 105.

This is where the cash conversion cycle comes in. It’s calculated as:

Cash cycle = Operating cycle – Accounts payable period

75 days = 105 days – 30 days

So, the company’s funds are committed for 75 days—the time between paying suppliers and receiving payment from customers. A shorter CCC means a firm recovers its cash faster and can reinvest it more quickly.

Industry Comparisons: How Companies Perform

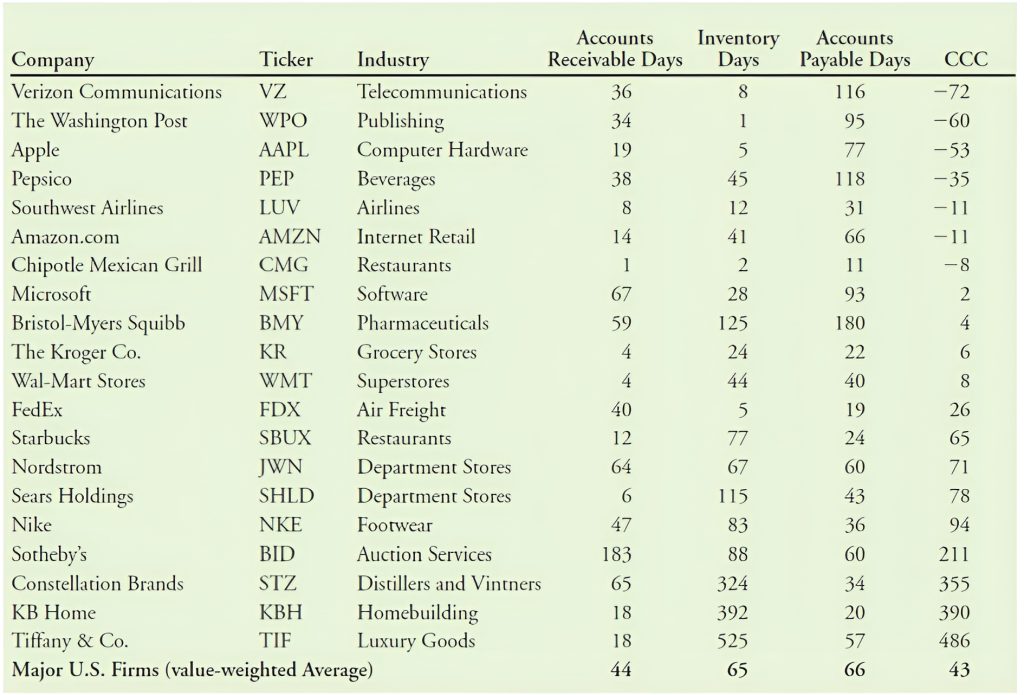

As seen in an earlier example, companies across different industries manage their cash conversion cycles in distinct ways. The table below presents the CCC data for a selection of US firms from various sectors:

Financial Intelligence: A Manager’s Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really Mean by Karen Berman and Joe Knight

Some firms—such as Walmart and Chipotle Mexican Grill—typically operate with very short or even negative cash cycles. Since they sell primarily for cash and pay suppliers later, they often receive money from customers before spending on inventory.

Amazon and Southwest Airlines also benefit from negative cash cycles. Customers pay in advance—especially in airline bookings—which provides immediate liquidity. On the other hand, companies like KB Home and Tiffany & Co. have lengthy CCCs because their products require long production and sales periods. As a result, they tie up capital for hundreds of days before recovering cash.

This variation highlights how the nature of a company’s operations—including inventory turnover and credit terms—plays a central role in working capital management.

Why the Cash Conversion Cycle Matters

A company’s cash conversion cycle is a powerful indicator of how efficiently it manages its working capital. A shorter CCC allows a firm to generate cash more quickly and reduces its need for outside financing. This improves financial flexibility and overall performance.

While long cash cycles may be unavoidable in capital-intensive industries, most companies strive to reduce their cycle times by tightening inventory management, shortening receivables collection periods, or negotiating longer payment terms with suppliers. As the industry comparison shows, companies that manage to operate with negative CCCs have a significant liquidity advantage and greater freedom to grow without depending heavily on debt or equity funding.

Understanding and optimizing your cash conversion cycle is a critical skill for any finance professional—and joining the 365 Financial Analysis platform gives you the tools, insights, and real-world applications needed to master this and other key financial concepts.